Metaphors Blind You

The dangerous comfort of familiar frameworks

“What if this is the wrong way to think about it?” said the man walking to the front of the room.

He was one of the dozen members sitting in the room with me, discussing how to measure complexity. The discussion was already far outside my understanding. One sentence Ilya Sutskever (Co-founder of OpenAI) said to John Carmack (creator of Doom) led to the creation of this group, the 90/30 club.

I was in SF on a Monday night, read Ilya’s quote “If you really learn all of these, you’ll know 90% of what matters today,” and decided I wanted to listen in because I had nothing better to do.

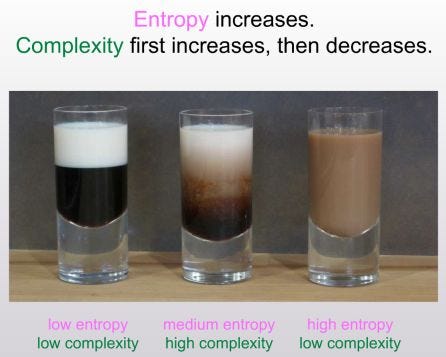

“I’m convinced this is a more accurate representation,” Ryo said once he got to the front, pulling out a nicely aligned Rubik’s Cube as he started to explain his point. I was lost. All I could think about was the original example of coffee.

This image from the paper was vivid in my head. I latched onto it. The entire conversation was about coffee moving from the left image to the right. Now, the only bit of understanding I had was being challenged. I was watching it disappear as the Rubik’s Cube got more mixed up in front of me.

Then Ryo said something I couldn’t ignore.

“Coffee shows you entropy. But a Rubik’s Cube might show you the path through entropy.”

He kept twisting the Rubik’s Cube just a little bit more. Then he started twisting it back.

The coffee metaphor was a beautiful explanation of entropy and complexity. But Ryo was explaining something different. He was showing how this could be navigated or better measured.

The coffee metaphor blinded me.

The Power of Familiar Frames

This is what metaphor models do. They explain and constrain. They spotlight one part of reality while creating a shadow on others.

Steve Jobs understood this when building the Macintosh. He chose the desktop as his metaphor for the computer interface. Not a command line. Not a filing cabinet. A desktop.

“People know how to deal with a desktop intuitively,” Jobs said. “If you walk into an office, there are papers on the desk. The one on the top is the most important. People know how to switch priorities.”

Brilliant. Like coffee, it took something intimidating and made it familiar. Files became documents. Directories became folders. Deleting something meant dragging it to a trash can.

This is skeuomorphic design. Using physical metaphors to make new things familiar. The desktop metaphor is why your grandma could learn to use a computer.

But my takeaway from the 90/30 club was the metaphors that help you adopt ideas can limit how you advance it.

What Metaphors Hide

In the 1850s, Édouard-Léon Scott de Martinville invented the phonautograph. Scott’s breakthrough in recording sound was inspired by stenography, leading him to “write waves instead of words.” However, this metaphor blinded him to the possibility of playback. Scott envisioned humans learning to “read” sound waves like shorthand, so he created a transcription service rather than an audio player. It took Edison, using a completely different metaphor, to unlock what Scott couldn’t see.

The metaphors determine what you can imagine.

I see this everywhere now.

“Climbing the ladder” explains promotions but hide lateral moves, skill stacking, or building your own elevator.

Building is a buzzword in tech. People build products, companies, and audiences. Building a house follows a blueprint. They have foundations. They finish. Technology is an infinite game though. Building makes you think about construction when we should be thinking in terms of evolution and experimentation.

User journey suggest a linear path. But users bounce around, circle back, forget and then return. The metaphor emphasizes funnels instead of ecosystems.

The metaphors you choose determine the problems you will solve.

The Dangerous Comfort of Good Explanations

Thinking about Ryo scramble and unscramble the Rubik’s Cube, I realized something uncomfortable. I have no idea which metaphors are blinding me right now.

I’m expanding my technical understanding growing my identity. My dominant metaphor has been building a bridge from product management to another discipline. Bridges are about connection, engineering, and crossing a gap.

But bridges are also one-way infrastructure. You build them one. They don’t adapt. Don’t grow. They definitely can’t change destinations or directions mid-construction.

Maybe I don’t need a bridge. Maybe I need a Rubik’s Cube. Or maybe I need to drop the metaphor entirely. Just describe reality for what it is: learning systems by building them, documenting what I uncover, connecting with people doing the same.

No metaphor. Just reality.

The man who pulled out a Rubik’s Cube gave me more than a better way to think about complexodynamics (I still don’t understand it).

He showed me that the most dangerous explanations aren’t the wrong ones.

They’re the good ones we never question by looking for better explanations.